The $1T Opportunity to Build the Next Amazon in Retail

Retail is a massive market, generating over $7 trillion annually in the U.S. Throughout history, significant technological advancements have driven major innovations in retail. We believe that the AI era offers an opportunity to create the next Amazon. This essay will analyze eight historical technological transformations of retail and then forecast five ways in which the AI revolution might transform retail in the future.

We wrote this for entrepreneurs, operators, technologists and investors who are interested in studying the past and understanding what the future might look like. We hope that sharing this thesis will help instigate entrepreneurship and perhaps even help launch the next trillion-dollar retail company.

Ancient retail

Evidence suggests that early forms of trade and market-like activity emerged in the Middle East around the 7th millennium BC. Millennia later, Ancient Rome boasted some of the earliest documented permanent retail centers, such as the multi-level Trajan’s Market. Similarly, large-scale urban markets are well-documented in ancient China, for instance, the vast and highly organized East and West Markets of Chang’an during the Tang Dynasty.

For thousands of years, not much changed. Medieval Europe’s retail landscape was characterized by a network of open-air markets and periodic fairs. Weekly markets served local communities with perishable goods and daily necessities, often sold by street vendors, while larger, less frequent fairs facilitated regional and even international trade.

The Industrial Revolution caused a major transformation in the scale and nature of retail.

The Industrial Revolution and Beyond

The Industrial Revolution, beginning in Britain in the early 1700s and spreading to Europe and the U.S. by the early 1800s, reshaped retail:

Technology One: Manufacturing

James Watt’s improved steam engine (perfected in the 1770s) powered new machinery, while Eli Whitney’s cotton gin (1793) massively increased the availability of raw cotton. These innovations drastically increased the production of textiles, which in turn enabled the large-scale manufacturing of goods like ready-made clothing.

Retail impact: Off-the-shelf goods

This surge in affordable textiles led to a market with an unprecedented volume of products. The concept of buying fashionable, off-the-shelf garments in standardized sizes was novel. This flood of mass-produced goods created the need for new retail models, contributing directly to the rise of the modern store and the establishment of centralized “Main Street” shopping.

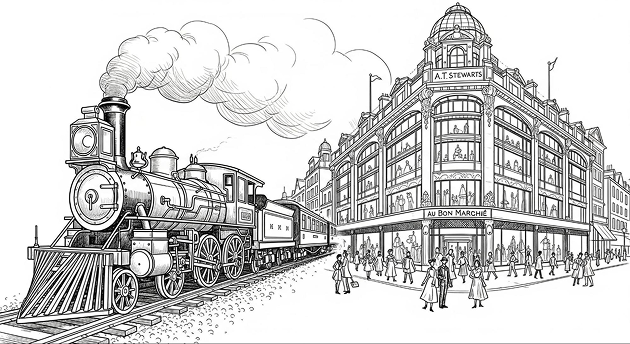

Technology Two: Public railways

The Stockton and Darlington Railway (England, 1825) was the world’s first public railway to use steam locomotives, initially for hauling coal freight. It began carrying passengers shortly after. In the United States, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) became the first U.S. chartered railroad for commercial transport of freight and passengers, opening its first 13-mile section in 1830.

Retail impact: The department store

Rapid urbanization, coupled with the logistical capabilities of the new railway systems, made travel to city centers easier and more common, paving the way for the department store. These large establishments changed retail by offering a vast array of goods under one roof. Au Bon Marché opened in Paris in 1838 and was transformed into what historians consider the world’s first true department store in 1852. This trend was followed by A.T. Stewart’s “Marble Palace” (New York, 1848), Macy’s (1858) and dozens of other iconic department stores.

Related innovation: Fixed pricing

For millennia, virtually every price was “up for negotiation” via haggling. Now that goods were mass produced (manufacturing) and a diverse population living in close proximity (urbanization), things changed. The adoption of fixed prices is most widely credited to American retailer John Wanamaker in 1861. Wanamaker, a devout Christian, believed that if everyone was equal in the eyes of God, they should also be equal in the marketplace. He introduced the “one price and goods returnable” policy at his Philadelphia men’s clothing store, “Oak Hall.” This revolutionary idea was accompanied by another innovation: the price tag.

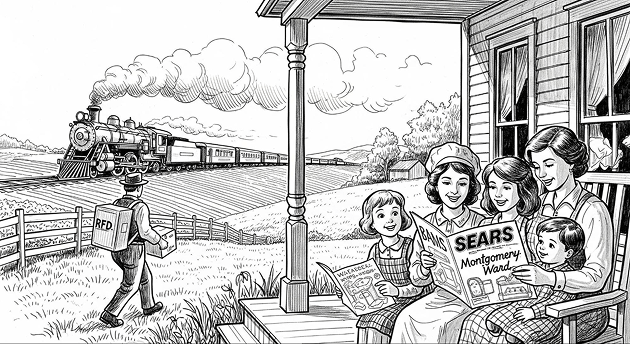

Technology Three: Rural railroads and telephony

Between 1870 and 1890, railroads were a dominant force in the American economy. During this period, an estimated 20% or more of the total gross investment in the United States was directed towards railroads. This extensive railway system was essential for rural “mail-order houses,” providing the logistical backbone to transport goods efficiently to and from their warehouses and connect them with customers in even the most remote areas.

Retail impact: Mail-order

Montgomery Ward launched the first mail-order catalog in 1872, followed by Sears, Roebuck and Co. in 1894. This coincided with the rise of telephony, patented in 1876, which became a mainstream communication tool by the 1920s, accelerating the mail-order trend. Consumers could order products they saw in catalogues either through mail-in forms or over the phone, then have those products delivered to their front door. In its time, mail-order was the “Amazon,” allowing consumers nationwide to choose products from a catalog and receive home delivery with unprecedented speed.

Related innovation: Standard rates

The growth of these businesses was significantly boosted by federal government initiatives, such as Rural Free Delivery (RFD) in 1896. The U.S. established the Parcel Post service in 1913, setting standardized rates for shipping packages. Prior to 1913, the shipment of goods was largely controlled by private express companies, which held monopolistic power and catered to urban centers. For the first time, Americans could send packages weighing up to 11 pounds (a limit that was quickly expanded) through the U.S. Mail at standardized, affordable rates. This seemingly simple change had a number of profound and lasting impacts including the explosion of the mail-order model.

Technology Four: Cash registers

James Ritty invented the first mechanical cash register, dubbed the “Incorruptible Cashier,” in 1879 to combat theft by his staff. After buying the patent, the National Cash Register Company (NCR) was formed, and by the late 19th century, these devices had become standard equipment in retail stores. The technology took another leap forward in 1906 when Charles F. Kettering, an engineer at NCR, developed the first cash register powered by an electric motor.

Retail impact: The rise of chain stores

The financial control and operational consistency provided by cash registers helped enable the proliferation of chain stores. By allowing for standardized cash handling and sales tracking across multiple locations, owners could more effectively manage a geographically dispersed business. This laid the groundwork for a massive expansion of chain stores in the early 20th century. The 1920s saw a dramatic surge in the growth and prominence of these chains. This was the era of American retailers including Woolworth’s, J. C. Penney, and Walgreen Drug.

Technology Five: Automobiles

Henry Ford introduced the Model T in 1908, beginning America’s love story with the automobile. By 1930, over 50% of American families owned a car, a figure that climbed to nearly 80% by 1960. This mass adoption, particularly after World War II, fueled rapid suburbanization and gave families the mobility to shop beyond traditional downtown areas.

Retail impact: Malls

The new car-centric lifestyle paved the way for the suburban shopping mall. The first fully enclosed, climate-controlled mall in the United States, Southdale Center, opened in Edina, Minnesota, in 1956. Southdale’s model was immensely influential, and mall construction boomed in the following decades. By the 1980s, malls had become centers of American commerce and social life.

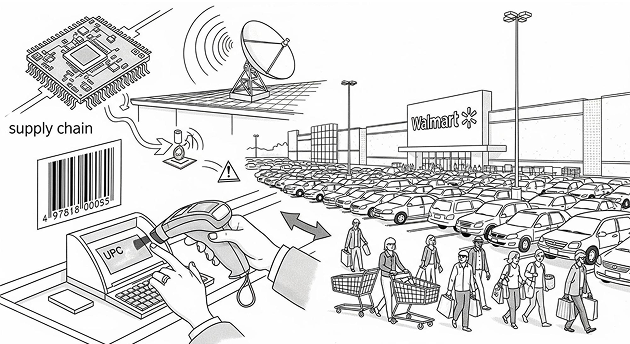

Technology Six: Microprocessors and supply chain systems

The invention of the microprocessor was a critical enabler for modern retail logistics. This technology powered the point-of-sale systems that made the Universal Product Code (UPC) commercially viable. First scanned in a supermarket in 1974, the UPC, combined with barcode scanners, advanced checkout and inventory management. As retailers scaled, managing vast quantities of goods became a major challenge, leading to the development of sophisticated Warehouse Management Systems (WMS), powered by increasingly powerful computers and algorithms.

Retail impact: Big-box dominance

The logistical precision enabled by computer technology was a key driver for the explosive growth of “big-box” retailers. Walmart, founded in 1962, grew from a regional chain to a global powerhouse by pioneering these systems. In the late 1960s, Walmart began using IBM computers to track inventory, and by the early 1980s, it had launched a private satellite network to link its thousands of stores to its headquarters, enabling real-time data analysis and highly efficient, direct-from-supplier ordering. This era of tech-fueled logistical mastery saw the rise and expansion of other major big-box chains, including Target (1962), Best Buy (1966), The Home Depot (1978) and Costco (1983).

Technology Seven: The World Wide Web

Though the internet was many years in the making, the World Wide Web was launched in 1989. The release of user-friendly web browsers, like Mosaic in 1993, made the web easily accessible to the public and spurred its widespread adoption. This led to the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and global adoption of the internet in the coming decades.

Retail impact: eCommerce

The foundations of modern e-commerce were laid in the mid-1990s with the launch of pioneering online retailers like Amazon (1995) and eBay (1995). While the dot-com bubble burst around 2000, wiping out many startups, the companies that survived entered a period of sustainable growth. Throughout the 2000s, online shopping steadily gained consumer trust and market share, offering unparalleled convenience and selection. This continuous growth has profoundly disrupted traditional retail models, leading to ongoing, major shifts in the entire industry. In the U.S., online sales currently represent nearly 16% of total retail sales.

Technology Eight: Mobile devices and apps

While early mobile phones existed for decades, the introduction of the Apple iPhone in 2007 and its App Store in 2008 marked a pivotal shift in computing. This new generation of smartphones put powerful, location-aware computers with high-speed internet access into millions of consumers’ pockets. The subsequent app ecosystem created a platform for entirely new types of businesses and consumer behaviors built around mobility and real-time data.

Retail impact: On-demand economy and m-commerce

This shift is defined by two major trends: First, it enabled the rapid, on-demand delivery of retail goods. This gave rise to app-based giants that bring products to consumers’ doors in real-time, such as grocery delivery service Instacart (founded 2012) and food delivery powerhouse DoorDash (founded 2013). Second, it spawned a new breed of mobile-first retailers for physical goods, such as Chinese fast-fashion behemoth Shein and the rapidly growing marketplace Temu.

Exploring the era of AI

In the first section of this essay, we established that technology transforms retail. Major technology shifts have precipitated major changes in retail for hundreds of years. The rise of AI will open a very large opportunity to once again transform retail. We think there will be an Amazon-scale (+$2T) opportunity formed in the coming years. Here are some ways that opportunity could manifest.

Concept 1: “Consultative” Purchasing

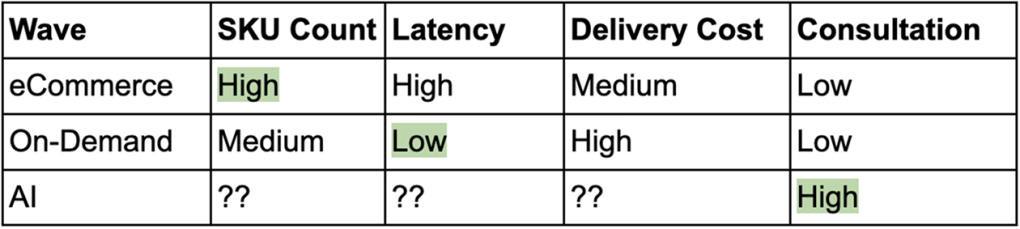

Each major technological advancement has introduced a new dimension to shopping. Consider three waves:

- eCommerce: The internet revolutionized access to information. The internet’s “superpower” is its ability to let consumers access endless information from anywhere with a computer. Amazon leveraged this by starting with the sale of books, a category that greatly benefited from offering nearly endless unique products (referred to as SKUs in retail). There are 170M unique books in the world, and “just” 120k SKUs at the average Walmart. While delivery was slow, the ability to access a wide selection without expert consultation was groundbreaking.

- On-Demand Economy: Mobile devices innovated on delivery speed. Mobile’s “superpower” was accessing information real-time from anywhere with internet service, and allowing for simplified navigation with GPS in every phone. DoorDash capitalized on this by specializing in food, a category that thrives on low-latency delivery. Food delivered in one hour is delicious while food delivered in one day is poisonous. While prices were relatively high compared to “free” Prime delivery, the immediacy of access was the key benefit. They didn’t innovate on SKU counts or consultation.

- AI: Artificial intelligence revolutionized analysis of information. AI’s super power is analyzing and answering complex questions. The future “retail giant” will emerge by focusing on purchases that necessitate expert question answering by consultative purchasers. Here, delivery speed and SKU count may not be the primary innovations; instead, the unique aspect will be the integrated consultation.

Case Study: Home Improvement

When a customer walks into Walmart, they generally know the product they want to buy. When a customer goes into Home Depot, they generally know the problem they want to solve but are open to consultation for how to approach the problem.

“Product to buy” purchasing (Walmart/Amazon): A significant portion of shopping on platforms like Amazon or at superstores like Walmart is based on clear intent. A customer knows they need a specific item (e.g., paper towels, a specific book, a new phone charger) and the platform’s goal is to fulfill that request as efficiently as possible with the best price and fastest delivery. While impulse buys occur, the initial visit is often product-driven.

“Consultative” Purchasing (Home Depot/Lowe’s): Home improvement retailers like Home Depot are fundamentally different. Customers frequently arrive with a problem, not always a product name. “My toilet is leaking” is a problem; the solution might involve a specific type of flapper, a wax ring or a new valve. These are items the average homeowner cannot name on sight. Similarly, “The paint in my house is off tone” is a subjective problem requiring guidance on colors, finishes, and tools. This journey is consultative and project-oriented.

A challenger built from the ground up on an AI-first model could certainly be disruptive. Home Depot is a $350B Market Cap retailer still focused on brick-and-mortar largely because of the consultative nature of home improvement.

Similar opportunities exist in other areas that generally benefit from consultation, including certain kinds of food and nutritional supplements, travel, clothing and health advice.

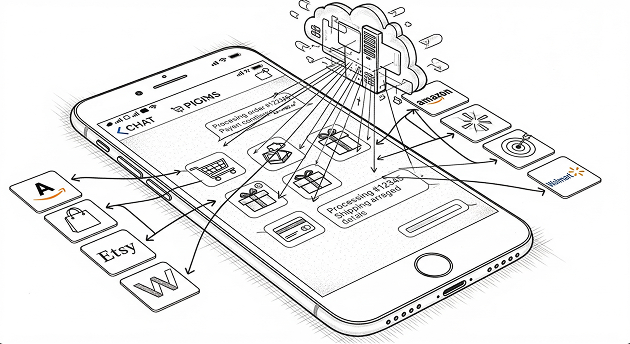

Concept 2: MCP servers

This scenario represents a highly probable future where individuals use AI chat platforms like ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Claude, Grok or Perplexity to research products. While they could complete purchases on Amazon, a significant opportunity emerges if transactions are completed directly within the chat interface.

This is where Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers become crucial. MCP servers are specialized programs that facilitate AI models’ standardized and efficient interaction with external tools and services. They essentially act as intermediaries, enabling independent companies to insert themselves into transaction flows orchestrated by AI agents.

By analogy, AI chat companies function as the new operating systems (similar to iOS). MCPs then become the “native apps” within this new ecosystem. Although users can still switch to the web-based Amazon.com, the convenience of an MCP integrated directly into the chat, like a native app on iOS, will likely win over consumers.

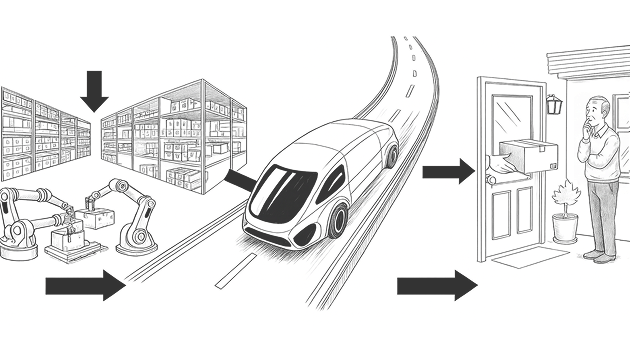

Concept 3: Predictive shipping

Amazon has made significant advancements in logistics, largely through the use of artificial intelligence, to drastically reduce delivery times. What once took several days now often takes a single day or even just a few hours in some metropolitan areas. This efficiency is achieved in part through predictive analytics for inventory placement, warehouse automation and optimized delivery routes.

The future Amazon could proactively ship products a customer might buy next to their home, with charges only applied if the customer decides to keep the item. Otherwise, it would be returned the following day. A recent initiative, Anthropic’s Project Vend, demonstrated an AI agent managing a store within their offices. While the agent mostly failed, it did attempt to anticipate customer needs and predict future purchases.

To achieve this future vision, the challenger company would likely begin with dry goods and staples, such as paper towels and toilet paper. By focusing on a high volume of specific SKUs, the company could establish a competitive edge and even dominate the market.

Concept 4: The roaming store

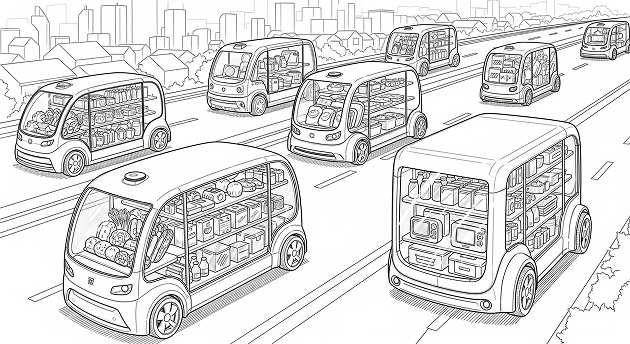

Waymo and Tesla Robotaxi are ushering in a new era of safe, cheap, always-on autonomous vehicles. This will change behavior. The Amazon of the future may have thousands of these vehicles constantly roaming, essentially storefronts on wheels. Like the ice cream trucks of yesteryear, this roaming store could provide a constant flow of available products.

Concept 5: Computer vision-based predictive shopping

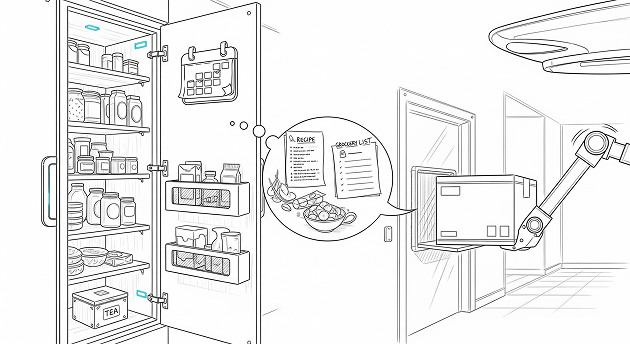

This approach, a variation of Predictive Shopping, emphasizes the physical world while posing greater privacy risks. Consumers would install more in-home sensors, such as cameras and connected routers. As sensor costs plummet, these devices could be placed anywhere, including pantries and cabinets. If a product, like tea, runs low, the system proactively reorders it. The AI, integrated with customer calendars, would identify events like dinner parties and, using pantry camera footage, formulate recipes based on available ingredients. Missing ingredients would then be automatically ordered by the AI. The paradigm shifts from active customer shopping to passive, on-demand product reception.

Conclusion

Retail, a massive $7 trillion market in the U.S. alone, transforms with each major tech leap. The AI revolution offers an opportunity to reimagine retail. This is a rally call for entrepreneurs, operators, technologists and investors to build the next trillion-dollar opportunity in retail. History gives us clues about how AI-native companies might change retail, but it’ll be up to visionary founders to make these experiences a reality. If you’ve got a vision and are building the next Amazon, email me at konstantine@sequoiacap.com.