The Arc Product-Market Fit Framework

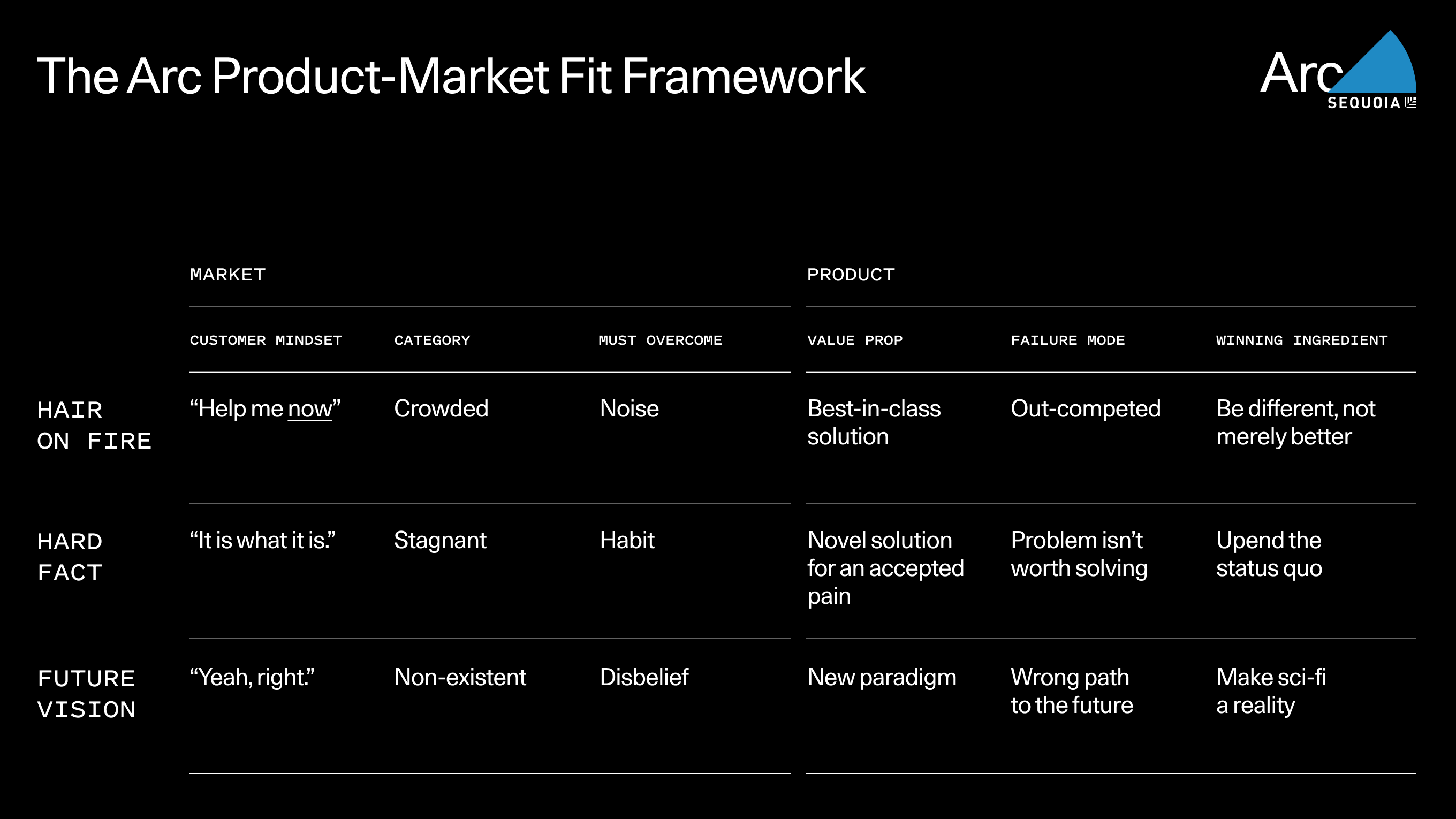

Finding product-market fit is the central quest of every early-stage startup. As we have seen over years of partnering with companies before they reached PMF, there are many ways of thinking about and approaching this quest. We walk founders through the following framework during Arc, our company-building immersion for pre-seed and seed stage companies. Rather than diagnosing whether you have product-market fit, this framework outlines three distinct archetypes of PMF which help you understand your product’s place in the market and determine how your company operates.

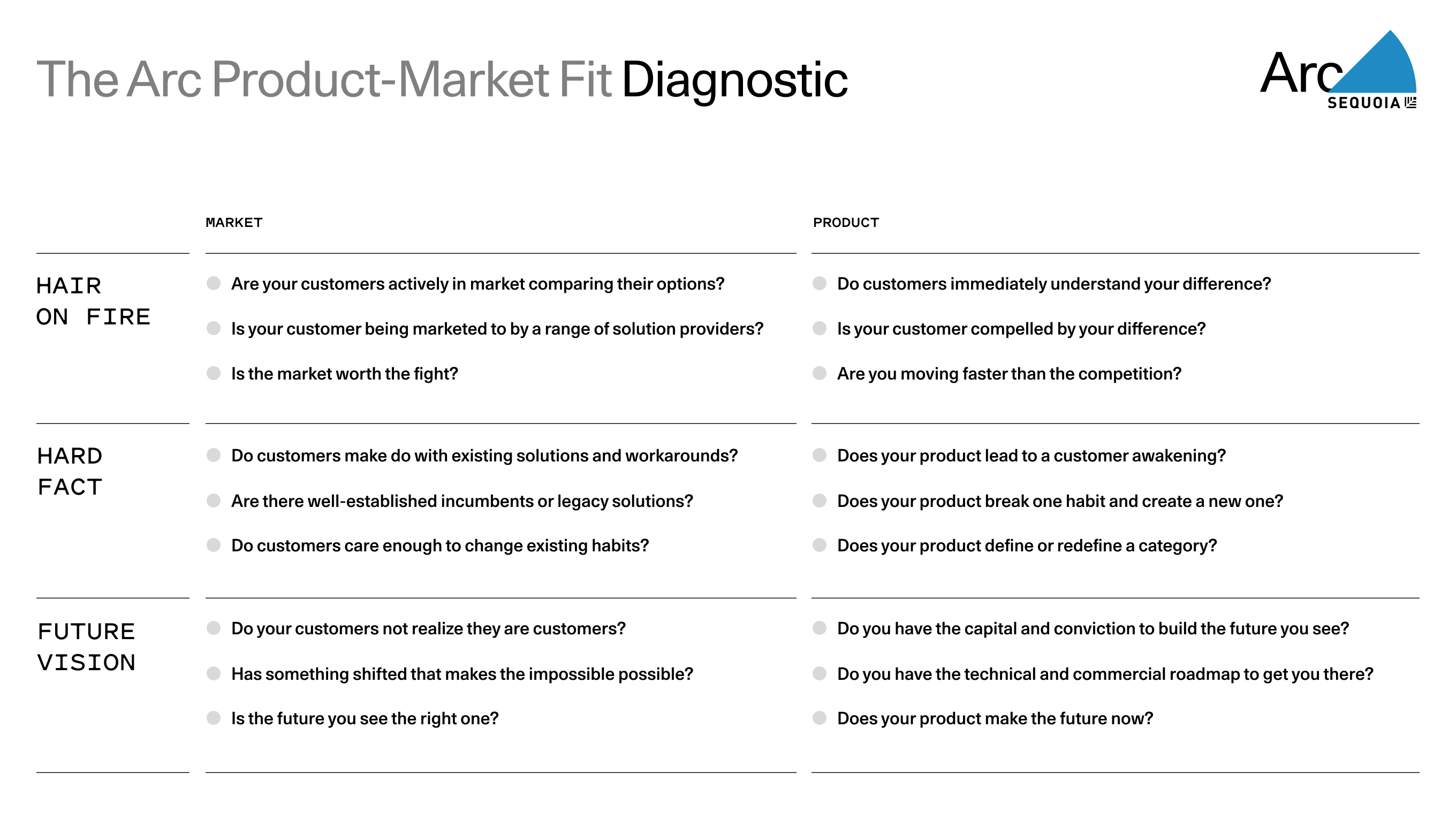

3 Archetypes of Product-Market Fit

Ultimately, product-market fit is about your product’s place in the world. There are different aspects to how your product fits into the world that you could hone in on—competitive landscape, the technical merits of your product, etc. We think the best way is to start by focusing on how the customer relates to the problem your product solves.

There are different kinds of problems, and different ways customers relate to them. We see three basic archetypes, each with its own distinct customer-product relationship dynamics.

Hair on Fire

You solve a problem that’s a clear, urgent need for customers. The demand is obvious. Because of this, your category is likely crowded with competitors vying for market share. Your customers are actively wrestling with the problem, and likely comparing existing products to solve it. To succeed in such a dynamic, you must rise above the noise. The only way to do so is by delivering the best-in-class solution. And best-in-class products stand out because they are different, not merely better. You can’t just be faster or cheaper—you need a truly differentiated customer experience to have a durable advantage.

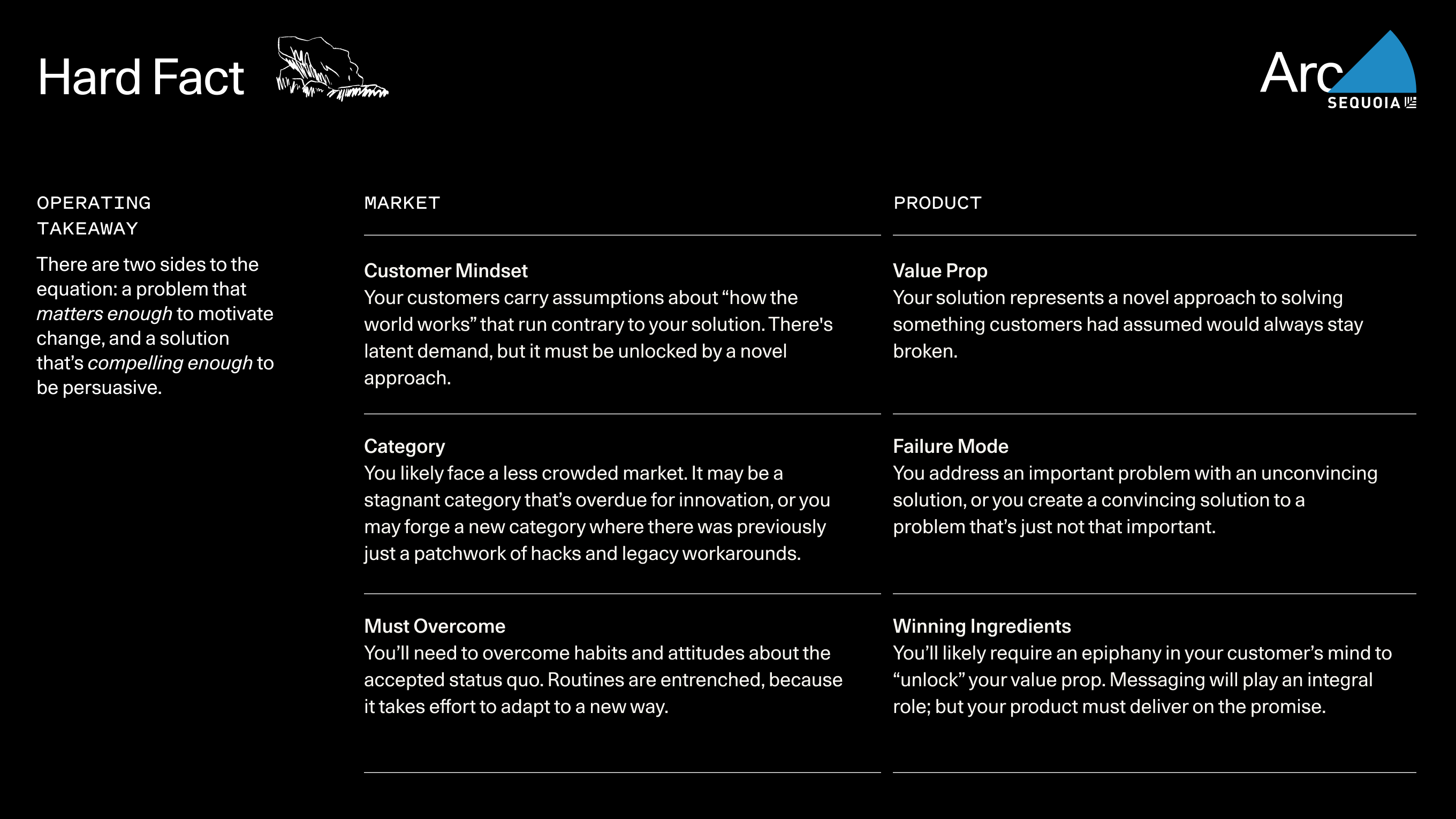

Hard Fact

You take a pain point universally accepted as a hard fact of life, and see that it’s merely a hard problem that your product solves for the customer. Your customers have resigned themselves to just living with the problem. They’re not urgently engaged with trying to solve it. The status quo is just how it is, and change doesn’t seem like an option. You upend how things are done with an unexpected approach: Facts can’t be changed—but problems can be solved. The challenge to overcome is force of habit. Customers will have to change their current behaviors, and inertia is powerful. You need an approach that’s novel enough, for a problem that matters enough, to be worth making a change.

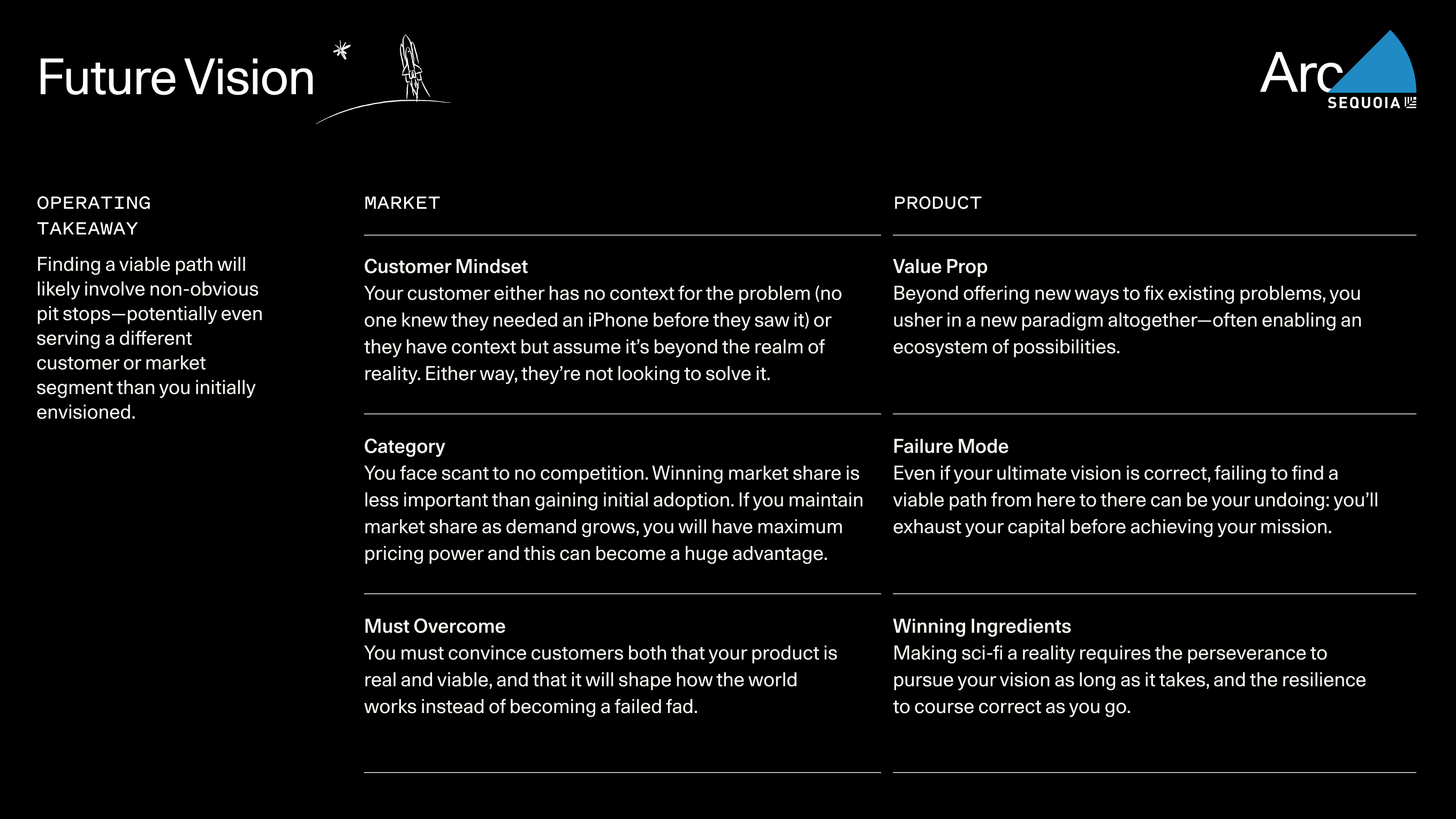

Future Vision

You enable a new reality through visionary innovation. It sounds like science fiction to customers, either because the concept is familiar but sounds impossible (like abundant cheap energy from nuclear fusion) or because no one ever imagined it (like the iPhone). Customers are not only not trying to solve the problem, they are either oblivious to it or predisposed to think it’s a pipe dream. Either way, the obstacle is disbelief: Customers must believe that your product represents a whole new paradigm—often with its own ecosystem. (The iPhone wasn’t just a device; its App Store was a new way of interfacing with the internet. Tesla isn’t just a car; it’s a network of cameras and self-driving software that’s a new driving experience.) Customers must find the paradigm and its possibilities irresistible. As we’ll discuss below, this path is often long, and finding the right route with the right commercial opportunities along the way is usually critical.

How to Operate in Each Path

Once you understand these archetypes, you can self-identify which path your company is on. Many founders we encounter in Arc assume they’re supposed to be in the Hair on Fire path. They have absorbed the adage to listen to what customers need. That’s good advice. But it often comes as a revelation that Hard Fact or Future Vision dynamics are viable options for finding PMF.

Hopefully you’re already working on a problem you have a unique advantage in solving. Your path, however, will be defined by how your customer relates to this problem (and how they feel about your solution). You can find success on any path—but each brings a distinct set of operating priorities that are essential to understand.

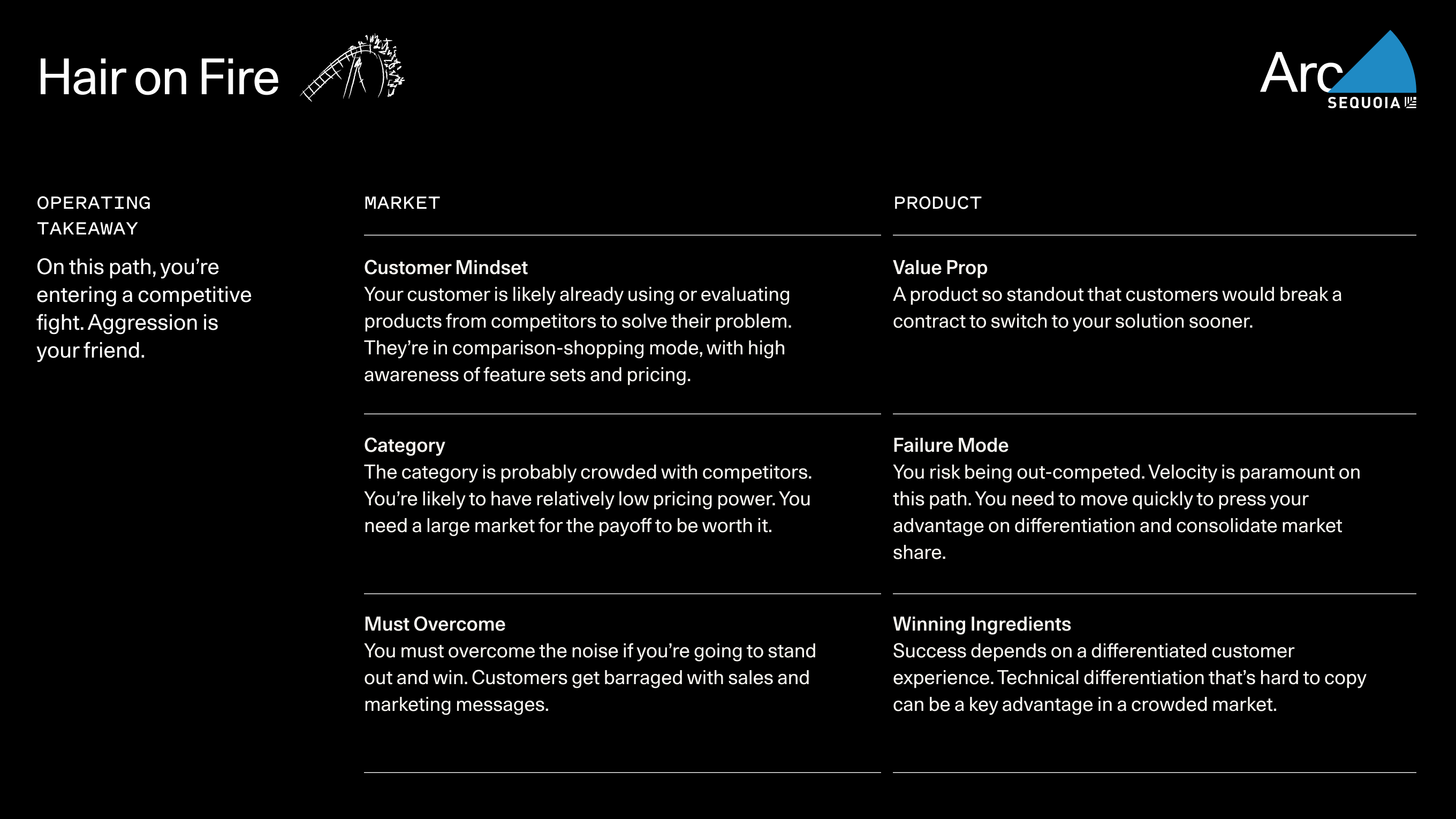

Path 1 – Hair on Fire

The Hair on Fire path requires both a great product and a great go-to-market effort—in quick succession. This combination of solution, selling and speed is the key to overcoming the competition.

Hair on Fire – Case Studies

Along with product velocity, one hallmark of companies that break through to find success in the Hair on Fire path is the ability to aggressively out-maneuver the competition.

Assaf Rappaport and his Wiz co-founders had previously founded Adallom together. For their new company, they were intrigued by the problem of cloud infrastructure security—but it was already a crowded space with incumbents like Palo Alto Networks and startups like Orca Security offering products on the market. However, when they interviewed CISOs, the topic kept surfacing at the top of everyone’s wish list. There was evident demand in a large market—but it took some digging to find the opportunity for differentiation. Most cloud security products relied on agents, a piece of software that needs to be installed in every server in order to monitor it. Wiz conceived an “agentless” solution that not only reduced friction and headaches, but surfaced vulnerabilities more effectively. Even better, once connected it could surface those vulnerabilities in the course of a 15-minute customer demo. Assaf and his team found their advantage, and floored the accelerator, aggressively out-maneuvering the competition: engineers built the product during their workday Israel time, and worked double-duty as sales reps at night—daytime in the U.S. They went from $0 to $2.8M in a single quarter and reached $100M in ARR in 18 months, setting a new record for the fastest-growing software company, ever.

When Parker Conrad founded Rippling, he was entering a large Hair on Fire market. Every company needs HR software, and this urgency was reflected in the steep competition: there were already at least half a dozen incumbents fighting for market share. In fact one of them was Parker’s own previous company Zenefits. Why bother? Because his deep expertise meant he knew what needed to be done differently: While other providers stitched together disparate datasets to offer a single platform for HR and benefits, Rippling’s approach was to build a unified database. This foundation layer for employee data could then “ripple” out to any aspect of the employee experience, from benefits to expenses to device management. Their technical advantage created a different experience for HR, finance and IT administrators, which allowed Rippling to stand out and quickly grow market share in a field of incumbents. And their strategy of bundling the widest set of employee experiences gave it pricing power even in a Hair on Fire dynamic where price leverage can be challenging for new entrants.

Path 2 – Hard Fact

The Hard Fact path entails getting customers to re-evaluate and change the way they approach a current process. This requires first educating the market, and then capturing the opportunity.

Hard Fact – Case Studies

Your novel approach may replace an existing market (like Salesforce moving CRM to the cloud) or it may create a new market (like Uber reimagining the taxi experience as a rideshare marketplace). Either way, you will likely face less competition on the Hard Fact path because the difficulty of changing the status quo has discouraged other founders from taking on the problem. To succeed, Uber had to not only convince legions of everyday people to drive strangers around, but also engage with taxi unions, local regulations and labor laws. Others’ natural aversion to such difficulty means you’ll likely get more of a greenfield opportunity.

When Block (then Square) first launched, the hard fact they were addressing was widely known and acknowledged: “cash only.” For many small businesses or at any farmers’ market, there was no way to accept credit cards. Consumers would trudge off to find ATMs and merchants would often miss out on sales. Jack Dorsey and Jim McKelvey’s unique insight was that smartphones, which were just becoming ubiquitous, could be effectively turned into mobile credit card terminals. Square realized that this supposed hard fact of life was actually a hard problem that it could solve. But finding success meant getting the world to see it no longer had to live with this pain point, and to trust Square’s solution enough to adopt their new way. In order to activate this epiphany and win over early adopters who would evangelize the product, Square made an early decision to give its hardware and software away for free to merchants and figure out a business model later. Eventually, Square became a new standard.

In 2006, marketing mainly consisted of advertising, mailers and telemarketing. This put small businesses at a disadvantage, as these were all high-cost channels. Brian Halligan and Dharmesh Shah realized there was a new way: small companies could leverage the properties of the fast-maturing internet—blogs, social media, SEO, email newsletters—to reach audiences at a fraction of the cost of traditional channels. HubSpot’s suite of content, SEO and email management tools solved this problem for customers. But in order for customers to believe in their approach and begin adopting their product, HubSpot needed to crystalize the new way in customers’ minds—to make them aware that the old way was broken and could be replaced with something better. They did this by coining a term for their new way—“inbound marketing”— and even wrote a book about it. They were so effective at educating the market that the idea caught on and started a marketing revolution in the small business world, propelling HubSpot to product-market fit and beyond.

Path 3 – Future Vision

The Future Vision path has the most ways to fail and the fewest to succeed, but potentially the largest payoff. Taking this path requires endurance and the ability to attract and retain top talent for the long haul.

Future Vision – Case Studies

Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard said, “Life can only be understood by looking backward, but it must be lived looking forward.” Future Vision founders like Nvidia’s Jensen Huang, who took a tortuous 30-year path to reach the company’s founding ambition, can probably relate.

Nvidia’s initial vision was to uplevel what PCs are capable of with a 3D graphics chip that would transform the experience of using a computer. When Nvidia released its first chip, it was so ahead of its time that no one knew what to do with it. It took six years and three product lines to find product-market fit in an industry where the GPU enabled irresistible new possibilities: video games. While Nvidia’s original ambition wasn’t limited to the video game industry, it became synonymous with gaming innovation, with its GPUs powering both PCs and Xboxes. Were it not for that very productive pit stop—which propelled Nvidia to profitability and IPO—the company never would have survived long enough to power today’s AI revolution. In fact, they were teetering on bankruptcy before finding PMF in gaming. Thirty years from its founding, Nvidia is enabling a new computing paradigm as GPUs transform everything from data centers to cloud computing.

Future Vision products that fail to find PMF are often described as being “too early.” For instance, 11 years after Google Glass launched, augmented reality still hasn’t gone mainstream. This is precisely why finding pit stops with commercial traction along the way is so critical. Assuming your vision is correct and you can find a viable path, time is on your side with the Future Vision archetype: You can amass an insurmountable headstart while the world comes around to your paradigm. But finding the right pit stops can be difficult. You must act with imperfect information—“live looking forward,” as Kierkegaard said—and the pitfalls are always more obvious in hindsight. Oftentimes finding the right path means embracing unexpected turns, both with the technology you produce and the market you serve.

OpenAI is one of the most interesting Future Vision stories of our time. Its vision is to achieve artificial general intelligence (AGI)—long considered a pipe dream in technology circles—and to do so for the benefit of humanity. To achieve this, they started as a non-profit, since the founders thought the profit motive of a company would undermine their mission of human benefit. A few years into the journey, however, they realized that the cost of compute needed to innovate their large language models outstripped the fundraising capacity of even the best-connected non-profit. Their path required a turn into the for-profit sector. Adopting a more traditional startup structure brought funding as well as expectations for product launches—hence ChatGPT. It instantly found product-market fit in the iPhone paradigm of “I couldn’t imagine wanting it until I saw it.” Consumer demand for generative AI was nascent in 2022. In 2023, OpenAI generated $1.6B. While ChatGPT achieved the fastest adoption of any consumer technology product ever, for OpenAI it’s the pit stop they need on the way toward their real ambition.

Putting it All Together

Using the framework of these three paths—and keeping in mind that one isn’t better than the others—you can reflect on your own product’s place in the world. What path are you on? How do customers relate to the problem you’re solving? Are you thinking about the right category dynamics? What are your operating priorities? Do you need to optimize for velocity and scale, land an epiphany with early adopters, or strategize the pit stops in your journey?

The Quest Continues

Practice is always messier than theory, and as you apply this thinking in the real world there are several important nuances to keep in mind:

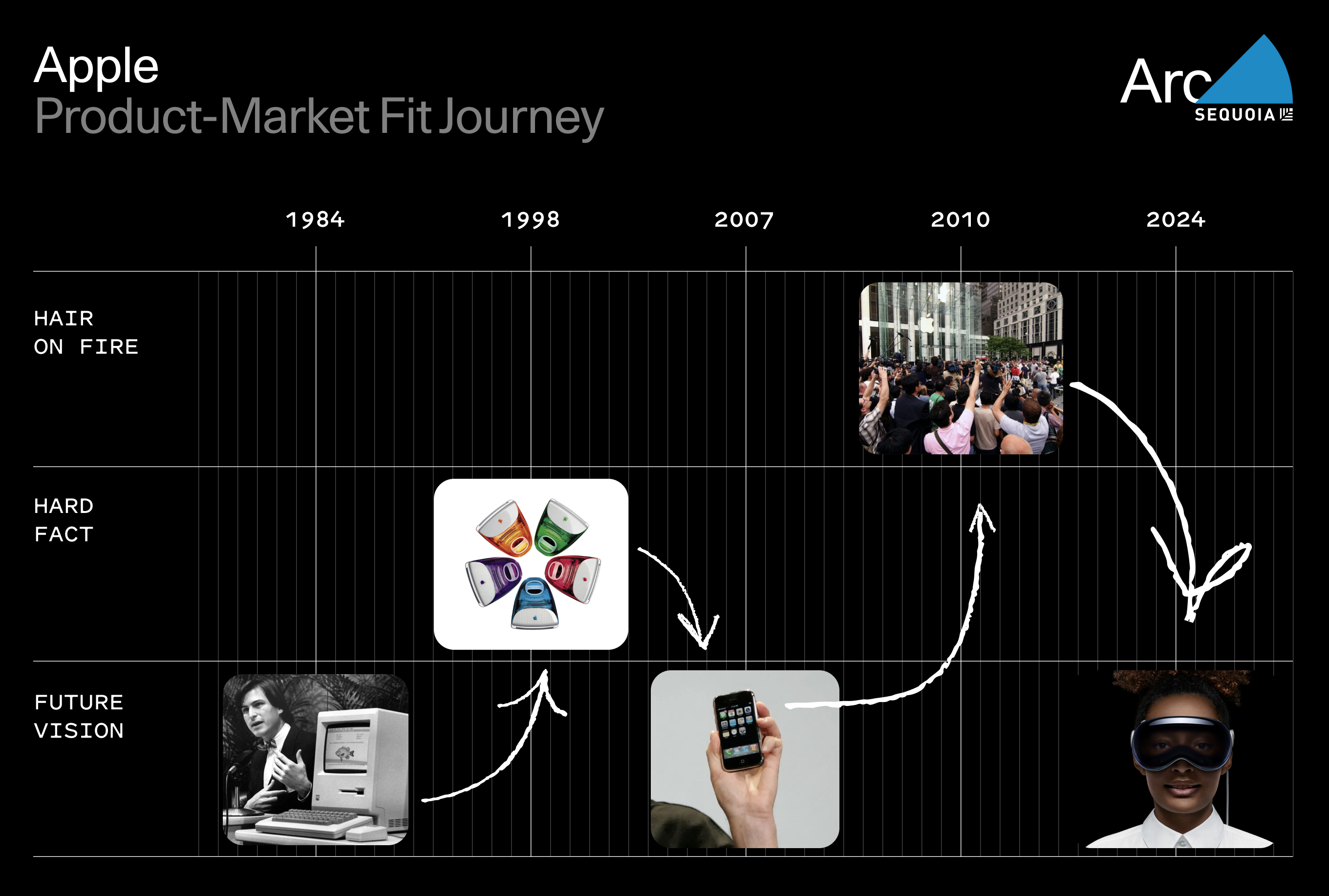

Product-market relationship dynamics are fluid. Over time, many companies end up moving from one path to another as they introduce new products or as customer attitudes change about an existing product and underlying problem. Some companies straddle two paths at once. The point of this framework is not to irrevocably set your path in stone; it would be a mistake to identify yourself too narrowly with any one of them.

Apple, for instance, started as a Future Vision. The company’s initial memo to Sequoia in 1978 acknowledged that there was zero demand for household computers. “Apple management,” it stated, “believes that most potential customers of 1980 do not today have the slightest interest in purchasing a home computer.” As they captured imaginations and grew in popularity in the ’80s, however, the category of personal computers was no longer a Future Vision. By 1998, with the launch of iMac, Apple addressed a Hard Fact: computers, while increasingly ubiquitous, were impersonal. The iPhone instantly found PMF as a Future Vision when Steve Jobs unveiled it in 2007. The smartphone category then quickly shifted to Hair on Fire dynamics and a flood of new smartphones entered the market. Apple managed to retain its dominance by defining the category, being right and continuing to innovate. Today, Apple is introducing yet another Future Vision with Apple Vision Pro. The device leverages the 10X advancements in sensors developed for the iPhone: the fruits of one product’s PMF journey can create seeds for the next. Will Apple Vision Pro enable entirely new experiences we can’t yet imagine, and fall squarely in the Hair on Fire path a few years from now? Time will tell.

Legendary companies string together multiple product lines that evolve through one path of product-market fit to another. While one product may plateau, the next product starts rising.

You can use this framework to orient yourself regardless of where you are in this cycle. PMF may seem like a destination you’re trying to reach—but keeping and expanding on it once you arrive is an ongoing quest that will last as long as your company does.